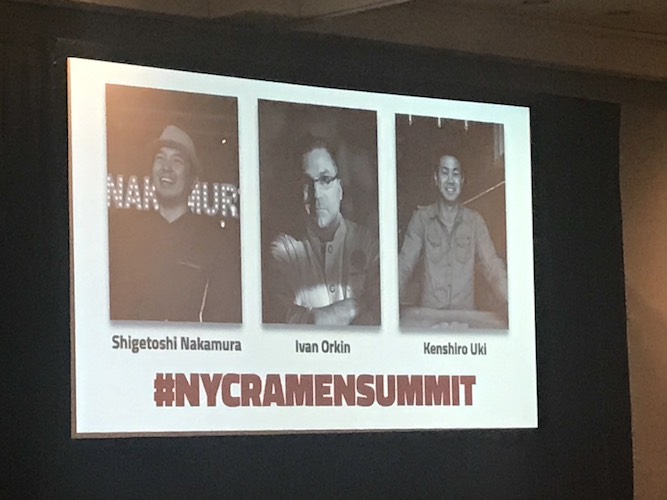

Ramen is perhaps the food most commonly associated with Anime and Japanese culture in the western world. It was only fitting that at Anime NYC, there was a panel dedicated to this well-loved and iconic noodle dish. The three panelists featured are some of the best known Ramen pioneers and restaurateurs this side of the Pacific - Japanese “Ramen God” Shigetoshi “Jack” Nakamura of Nakamura, revered artisan noodle-maker Kenshiro Uki of Sun Noodles, and Ivan Orkin of Ivan Ramen - a respected American Chef who has achieved culinary renown in Japan as well as the US.

The three panelists discussed their storied careers, the challenges and considerations of perfecting the art of Ramen in the United States, and what the iconic dish means to them - and took a few questions from the interviewer as well as the audience. They explored their individual paths in the culinary world, but also discussed the common threads that unite them as chefs who all cook and love the same dish. Sho Spaeth, who works as the Features Editor at Serious Eats, was the moderator.

Culinary journalist Sho Spaeth gave a brief lecture on the history of ramen as we know it - including highlights such as the first ramen noodles appearing in Japan in 1910 as a food manufactured for the consumption of working-class people, and the beloved invention of the instant ramen packet in by Momofuku Ando 1958. He discussed the advent of “first wave ramen” in the 80’s and 90’s - a movement to elevate the dish beyond a cheap, easy meal. “They started focusing on ramen as food that could be elevated to a gourmet status,” he told the audience. “The second wave of ramen happened in the 2000’s,” he explained. “That’s when ramen sort of got kicked into overdrive. That’s when premium ingredients started being used. That’s when chefs started deviating from the orthodoxy of what ramen used to be and creating new innovative techniques.” The panelists present were at the top of this innovative new school of ramen, Spaeth explained.

Ivan Orkin opened the famous Ivan Ramen Slurp shop on the Lower East Side in, 2013 after two successful restaurant ventures in Japan. “People were very amazed that he had somehow made Ramen his own,” Spaeth said. Orkin says that when he first enrolled in culinary school, the ramen scene here was “non-existent.” “There was no ramen. Nothing,” he said. “The place, Sapporo, served it but it was kind of cafeteria style.”

The famous chef who began his life in Japan as an English teacher shared in the panel that he was surprised to return to the United States. The period following the Tohoku earthquake in Japan was "a very upsetting time.” “Business kind of dropped off for a while because there were a lot of brownouts… they were cutting electricity to different areas of the city.” With a child to take care of and a book deal in the works, new business opportunities presented themselves back home and in time he wound up returning. ““It all sort of came together,” he told the panel. He added, “To tell you the truth, I thought I would die in Japan... I consider this temporary.”

He spoke about noodle quality - a commonly overlooked but very important component of ramen - and something that sets him apart. He says he remembers going to noodle shops in Japan to find that the soup was delicious but the noodles were less than stellar - so he decided to make his own. “”I used to call myself the apple computers of ramen. I do the hardware and the software - I do the noodles and the soup.” He says even in Japan, very few chefs make their own ramen noodles - less than 10%, Nakamura estimated. “I’m definitely a fine dining chef, so the whole process of figuring out how to make noodles, and broth... and everything was super exciting. ”

The veteran chef also gave the audience a lens into what makes ramen such a special dish to him, he referenced Chef Nakamura as inspiration. “I was listening to him talk about the spirit of Ramen, I’ll never forget,” Orkin said, recalling a time dining at Nakamura’s ramen renowned shop when he was just starting out himself. “It was very inspirational. Sometime later he said to me, ‘My goal is to feed a young child my ramen and watch that child eat my ramen until their a grownup.’ And I realized that after having a shop in Tokyo for 10 years I had kids I’d fed a bowl of ramen, their first bowl when they were like three years old or something…”

“This one girl, I met her when she was four or five or something, and now she’s sixteen.” His tone took on a heightened sense of enthusiasm as he continued, “When she sees me she hugs me and goes, ‘Uncle Ivan!’ It’s so cool because I’d been feeding her for years and I watched her grow up… it was such an exciting way to think about having a customer from childhood to adulthood, and knowing you fed them through all those different times and how exciting it is - it makes you part of your neighborhood.”

“Ken is probably the unknown hero of Ramen in New York City and in America.” Spaeth told attendees.”When he first took over Sun Noodles operations in LA in 2008, he hatched a plan to expand to the east coast which eventually leads to the proliferation of Ramen shops you see today,” he said. “He is the person to thank for the diversity of our Ramen ecosystem.”

Ken remembers growing up around Ramen because of his father’s noodle business and says he recalls observing a major difference between Ramen on the East coast and in Hawaii and California, where he worked. Uki said, “The difference that I felt when I came to New York was there are so much more tonkatsu - or pork bone ramen shops popular on the east coast. When I was on the West Coast, you had miso and shoyu- more varieties, and so I thought that was a pretty big difference.”

He talked about the events leading up to him establishing the first east coast Sun Noodle factory in New Jersey in 2011 and says his collaborations with Nakamura were instrumental in his success in doing so, from participating in Smorgasburg to a teach-in kitchen in the factory.

“We had this thing called Ramen Lab - it was very much education driven. But for us, it was just basically coming to New York with a goal of just making a name, and educating people more about ramen. I think that just grew into what we are today, which is making a lot of noodles for Ramen shops.”

Spaeth introduced Nakamura to the crowd as a “legend.” To those interested in traditional Ramen, the master chef needs little introduction. He opened his critically acclaimed restaurant, Nakamura-Ya in his home country of Japan when he was only 22, and went on to open another restaurant in New York City, Nakamura, on the Lower East Side in 2016. He is one of four Japanese chefs to be hailed as a “Ramen God.”

He expressed a strong interest in teaching people in the United States about different styles of ramen, pointing out that Tonkatsu is very popular here, but that is not the only style, especially in modern times. “Right now in Japan, there are a lot of varieties of ramen. I want to give them the choice of their ramen,” he said of westerners.

The Ramen guru talked about how tradition, as well as a place that has an influence on Ramen. When he first began his stateside restaurant, “Of course I want to present what is my ramen, what is Nakamura Ramen. It’s very hard to find a chicken based, a classical Ramen in the United States. I tried to make it here to show them what Japan’s ramen style is,” he said.

“That’s pretty important for ramen history. But still, ramen history is developing right now not only in Japan, even in the United States.” He emphasized that while tradition is important, the history of ramen as a cuisine is still being written. He hopes new locations will infuse their own local flavors into the food, providing the potential for new incarnations of the noodle dish. “I hope that in the United States the ramen is more… Ramen is basically local culture mixed. So the Hokkaido area has mostly miso ramen because the place is very cold. So they want thicker and very oily ramen there… so yeah, something like that,” he said. “I expect in the United States if they try to make Ramen with their ingredients. Ingredients are kind of the beating heart of cooking - not the chef.”

The panel closed with a few questions from the audience - mostly from aspiring chefs with specific quandaries hoping to perfect their noodle dishes. To one, Chef Orkin gave some sage advice, “The great part is there are no rules… I did a lot of trial and error and I have to tell you I made a lot of disgusting ramen before I got it right. So you know I always encourage people who want to cook, whether it’s ramen or anything else. The hardest part about cooking is when you’re trying to learn the people you love have to eat some crappy burnt food before you get it right.”

Final Thoughts

No comments:

Post a Comment